The recent success of the film Hamnet has generated a renewed interest in Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Considered a tragedy, the play also contains elements of mystery: it concerns itself not only with who killed the king, but also with what, exactly, is happening inside his troubled son’s mind.

Hamlet is consumed by “an antic disposition,” yet his behaviour defies any logical explanation. T.S. Eliot famously called the play a “dramatic failure” because it lacks an “objective correlative”: the sufficient chain of objects and events that would allow us to make sense of Hamlet’s emotional intensity.

Hamlet is sharp and perceptive, then suddenly erratic; capable of tenderness, then cuttingly cruel; resolved, then paralysed. He vacillates between certainty and doubt and we keep asking ourselves why his feelings seem so overwhelming. Yes, his father has been murdered. Yes, Claudius has seized the crown and married Gertrude with indecent speed. But the disturbance feels larger than these facts alone.

Some readings suggest his paralysis is bound up with a deeper tangle of desire and disgust: he cannot punish the man who has acted out what he himself cannot bear to name. “O, my offence is rank,” Claudius says, and Hamlet’s world begins to spiral out of control.

Eliot’s “objective correlative” names the way explicit signs can reliably evoke and explain emotion. Without these signs, Hamlet’s distraction can feel excessive, even hard to relate to. In other words: we can’t easily point to one clear cause that matches his feelings.

Today, our daily news feed can drive us to distraction at such a pace that we struggle to make sense of it all: images, statistics, and crises delivered at speed, engineered to hold our attention and trigger deep emotional reactions.

The result is not only constant awareness but preoccupation: anxiety, reactivity, fatigue, and very little room for proportion or sense-making. It can be exhausting, not because we don’t care, but because we care without any structure or order that helps us carry and interpret these feelings.

For educators, this isn’t just cultural commentary. It’s the classroom context.

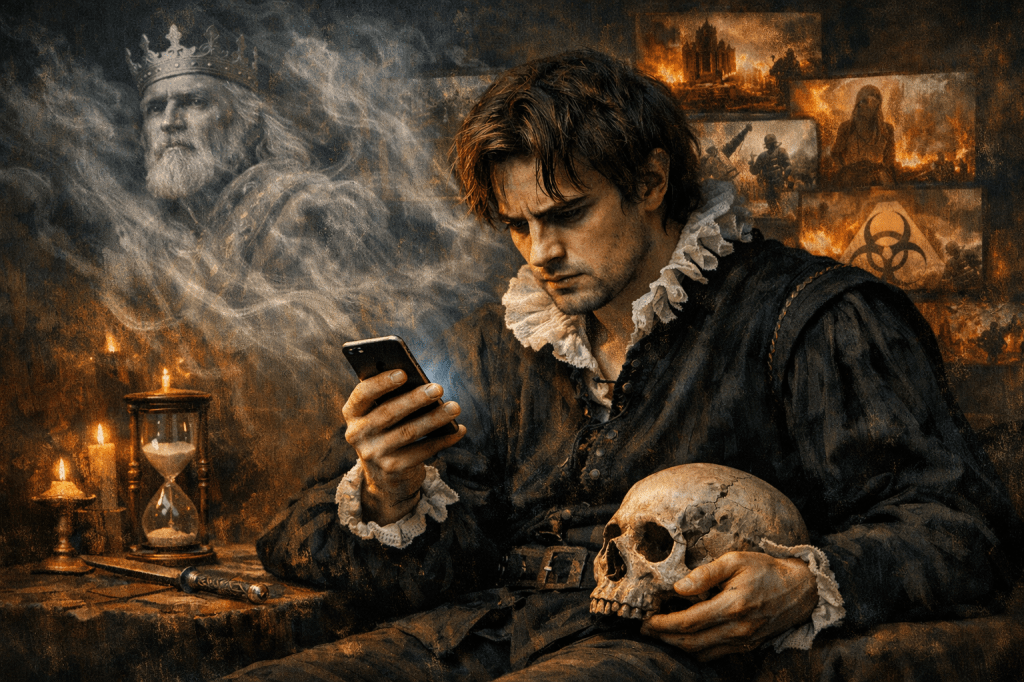

Shakespeare provides an image for this modern condition, almost too perfect to ignore.

King Hamlet is murdered when Claudius pours poison into his ear as he sleeps. That is how it can feel to live inside an overwhelming news cycle: a constant drip of catastrophe, moral indignation and poisonous outrage, poured into us relentlessly.

Not all of it is manipulation; much of it is real. But the delivery system is built for compulsion, even addiction. It produces something resembling Hamlet’s state of agitation: the sense that we must stay alert, must keep watching, must keep scrolling, even as our capacity to think and act steadily is eroded.

This challenge leaves schools with a daunting task. One of the central educational demands of the next decade will be to teach students how to take in the world without being poisoned by it: to maintain focus, sort knowledge from noise, and build meaning that outlasts a headline or a meme. Hamlet names the condition: “The time is out of joint.” The world will keep pouring itself into our ears; an education that is fit for this challenge has to teach young people how to filter, question, and respond with proportion.

Schools need to become places where agency is explicitly taught as an essential practice rather than a slogan. Technology can amplify meaningful learning, but we cannot outsource students’ attention, choices, and values to algorithms. Driven to distraction, learning how to learn with real agency has never been more important.